Welcome to the start of our “Architecture in Practice” journey. If you missed our introduction piece, check it out here: Architecture in Practice.

As we mentioned previously, early in her career, Tracy had the opportunity to act as both architect and developer (with her family) for three small spec houses in Santa Maria. This seems like a good time for us to revisit that process, and the three houses, as we embark on our new development journey with these questions in mind:

- Is architectural training an asset or a liability for a developer?

- What are the pitfalls of an architect-designed spec house in a tract home market?

- How do life and architecture co-exist?

Some Background

Santa Maria is a small-ish city in the Central Coast of California. It is a largely agricultural community, and the median income for a family in 2000 was under $50,000. In the early ‘90s, to help provide more inexpensive housing, the city decided to purchase a huge area of land, subdivide it, and then sell off the individual lots to developers for an expected future home sales price between $119,000 and $125,000.

At the time, the majority of homes built in the city were developed in large tracts by just a few developers. As a result, most houses looked alike and had similar floor plans. We thought the city’s intention for this new development process was to create some variety in the homes throughout the city…Boy, were we in for a surprise!

Is Architectural Training an Asset or a Liability?

Someone once stated that the difference between the way an architect and an engineer approach a design problem has to do with rules. The engineer wants to know what the rules are, so that they can adhere to them. An architect, on the other hand, wants to know what the rules are so they can break them.

Architects are trained to question everything – if this is how it has always been done, is there a better way? We are an optimistic group always trying to improve on a system, a way of living, a way of building, etc. However, this can put an architect ahead of the general population. We have been known to provide new and untested solutions to problems that may or, (let’s be honest) may not exist in the homebuyer’s mind. Tracy is no exception to this rule.

Tracy had the following goals for their three Santa Maria homes:

-

Rethink the garage location and access

Conventionally, the nearby homes placed a garage right on the front of the house with very little room for windows or rooms facing the street. Don’t people want to watch their kids playing in the front yard on the quiet residential street? Tracy decided to tuck the garages at the back of the lot with a shared driveway to minimize paving and maximize the front yard and landscaping opportunities.

-

Maximize height and volume to make the houses feel bigger inside

In order to meet the target sales price, the houses had to be small. To help offset the small floor plate, Tracy designed the living spaces with high ceilings to provide extra drama and a sense of open space.

-

Design a flexible floor plan for a variety of family configurations

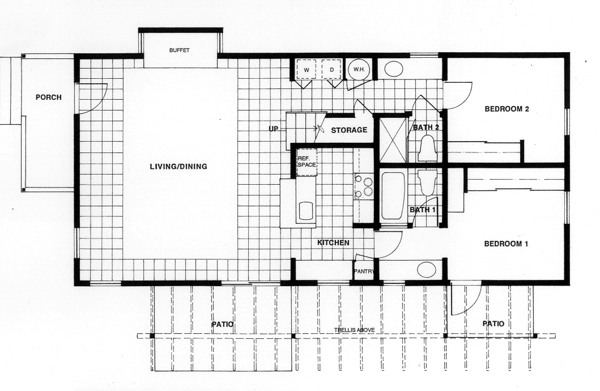

All of the other houses on the market assumed a traditional nuclear family with a master suite and two smaller bedrooms. Tracy was interested in providing options for other family types: a single parent with a grandparent and one to two children, two unrelated adults sharing a house, as well as the traditional nuclear family.

An Architect-Designed Home in a Tract Home Market

Tracy and her family were the first to purchase lots in the new tract, the first to build, and theirs were the first homes to come to market.

One of the tricky parts of this development was the “high” cost of the land. Instead of Santa Maria selling the land at a low price to encourage more affordable development and neighborhoods, the city wanted to make a profit on this whole process. The difference between the cost of the land and the target sales price for the houses left just about $90,000 for design, permitting, and construction — a square foot cost of about $63/sf! Even in the mid ‘90s, this was ridiculously low.

Tracy employed a few design strategies to keep the costs down:

-

A rectangular plan with only 4 corners

-

Single gable roof constructed with pre-fab scissor trusses.

-

Add a loft bedroom over the kitchen and bathrooms.

The trusses not only made for speedy installation, but allowed for a vaulted ceiling on the inside. The addition of the loft kept the overall floor plate (and thus, foundation) small, but added valuable, habitable space in what would have otherwise been an attic.

The result: a detached garage in the rear, a double-height living/dining room, the loft bedroom, and “flexible bedrooms” that could be configured to include a bathroom (to create a master suite) or exclude the bathroom for a shared restroom. In summary, their houses looked nothing like the other homes in the area.

So how did this all work out?

The rest of the lots in the neighborhood sold to one developer, who built the “normal” Santa Maria house. All of these identical houses followed the standard pattern: one story with the garage fronting on the street, and a floor plan with a master suite and two smaller bedrooms.

When Tracy’s homes went on the market, she snuck into a real estate showing at which the agent had no idea how to sell these atypical homes. The agent APOLOGIZED to the potential buyers for the strangeness of the design, and tried to make light of the “weird” high ceilings! Nevertheless the houses all eventually sold, and the development broke even.

Fast forward twenty years to a recent visit to Santa Maria. Tracy had the opportunity to revisit the site and the houses. Much to her amazement, two of the three have been remodeled beyond recognition! None of the other homes in the tract were touched, just hers! This begs the question: were the architect-designed houses so deficient that they had to be changed OR did they provide a framework for owners to modify as needed to accommodate the specifics of their lives?

When architect Le Corbusier was faced with a similar experience (his Pessac housing project in France has been remodeled repeatedly by owners over the years), he noted: “You know, it is always life that is right, and the architect who is wrong.” An architectural critic, Philippe Boudon, concluded that “the modifications carried out by the occupants constitute a positive, and not a negative consequence of Le Corbusier’s original conception. Pessac not only allowed the occupants sufficient latitude to satisfy their needs, by doing so it also helped them to realize what those needs were.” (1)

When architect Le Corbusier was faced with a similar experience (his Pessac housing project in France has been remodeled repeatedly by owners over the years), he noted: “You know, it is always life that is right, and the architect who is wrong.” An architectural critic, Philippe Boudon, concluded that “the modifications carried out by the occupants constitute a positive, and not a negative consequence of Le Corbusier’s original conception. Pessac not only allowed the occupants sufficient latitude to satisfy their needs, by doing so it also helped them to realize what those needs were.” (1)

Perhaps all the changes to the Santa Maria homes created the best possible outcome, after all. An architect can provide the catalyst: by questioning traditional wisdom, we give occupants the freedom to imagine other options for themselves. We don’t always get spec houses right (the architect’s ideal house pre-supposes that others want to live the way we think they should), but perhaps we can stimulate a dialog between house and occupant that allows the two to co-exist.

Stay tuned to hear about the lot we were able to purchase and the limiting development factors that we were willing to plan for.

Keep an eye out for these upcoming posts:

- 5 Red Flags When Looking for a Vacant Lot

- Building in LA: First step… Find a lot

References: