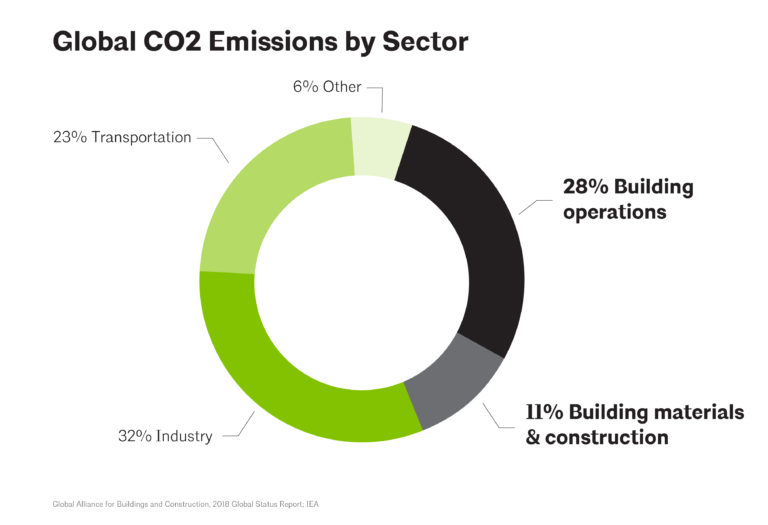

The building sector is a major polluter.

In fact, in 2018, if we include energy consumption and emissions from the manufacture of building construction materials, our industry accounted for the largest share of energy use and emissions, globally.

Following on the heels of the American Institute of Architects’ recent symposium on climate change, Tracy A. Stone Architect (TAS) is continuing our Ethics of Architecture series by looking at various ways that architecture and construction can improve our industry’s impact on the environment. If we are going to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and get climate change under control, the building sector is going to have to make some big changes. By 2050, the US Mid-Century Strategy goal is to reduce US building sector Co2 emissions by 80%, as compared to 2005. Much of this will come from better efficiencies, and a switch to renewable sources for electricity, but architects are going to have to do their part by changing the way we think about materials and structures.

Following on the heels of the American Institute of Architects’ recent symposium on climate change, Tracy A. Stone Architect (TAS) is continuing our Ethics of Architecture series by looking at various ways that architecture and construction can improve our industry’s impact on the environment. If we are going to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and get climate change under control, the building sector is going to have to make some big changes. By 2050, the US Mid-Century Strategy goal is to reduce US building sector Co2 emissions by 80%, as compared to 2005. Much of this will come from better efficiencies, and a switch to renewable sources for electricity, but architects are going to have to do their part by changing the way we think about materials and structures.

Our last blog article, Build Better, for Forest’s (and our) Sake!, reviewed the ethics of building with wood, and concluded that, with an effort to sourcing and using FSC-certified products, wood is an excellent building material from a sustainable design perspective. But are there other carbon-neutral, or less carbon-intensive materials out there? Happily, the answer is “Yes”.

I want to use better products. Where do I start?

The most carbon-intensive building materials are concrete, steel and aluminum. According to AIA’s Blueprint for Better Campaign, together those materials accounted for approximately 22.7% of global Co2 emissions by the building sector in 2017. The building industry can have an immediate impact on this number by looking at realistic alternatives to these three materials. Most savvy climate activists don’t want to eliminate concrete and steel entirely – after all, they are durable materials that fulfill important structural and life-safety roles. The challenge is to use them only when most appropriate and to find alternatives wherever possible.

What could possibly replace concrete?

Concrete has been around since the Romans and is used in almost every building built today. However, carbon dioxide emissions from the production of concrete are so high that if concrete were a country, it would be the third-largest emitter of Co2 (behind China and the US). The majority of these emissions come from the production of cement, the binder in concrete. A key strategy for reducing emissions, then, would be to find a way to reduce (or eliminate) cement in the mix (rather than to replace concrete entirely). Is this possible? Fortunately, this problem is well known, and there are a few options to consider:

- Replace part of the cement with an industrial by-product (like Fly Ash).

- Pay attention to the concrete mix. There are ways to reduce the amount of cement in a concrete mix, and designers and engineers can directly impact this.

- Use Hempcrete instead of concrete: a mixture of hemp hurd, lime and water that is strong and earthquake-resistant, and has a lower carbon footprint than concrete.

- Scientists are studying the use of clay to replace traditional cement in the mix. This method uses less energy, and avoids the emissions from decomposing limestone, a major source of GHG.

What about concrete block? Any alternatives here?

Concrete masonry units (CMUs), are often seen as a less-expensive alternative for constructing walls where concrete might otherwise have been used. CMUs are frequently used in retaining walls, warehouses (like the TAS office), and were a popular building material for the 1950 modernists who used textile blocks in places like Palm Springs to give a durable, patterned effect to their houses. However, CMUs have the same emissions problem as concrete. They are made with cement, and therefore their manufacture also contributes to the world’s overproduction of Co2. The good news is that there is a beautiful alternative now on the market: the Pasquale Watershed Block is comprised of quarried materials from Sonoma County. According to the manufacturer, this material uses significantly less cement (up to 50% less) than ordinary CMUs.

Steel is strong, flexible, fire-resistant, and my engineer says I have to use it. What now?

Again, it may not be possible to entirely replace steel as a building material. But we do have a couple of options to reduce the carbon footprint of this ubiquitous material:

- Steel is highly recyclable, and, as a result, steel in North America contains an average of 25% recycled content. Structural steel can have as much as 93% recycled content. And, steel has an unlimited capacity for being repeatedly recycled. Pushing manufacturers to continue to recycle, and to increase the percentage of recycled steel is good for everyone. This means that we have to make sure that all steel is available for recycling at the end of its life…a burden that we, the consumers, along with the construction industry, share.

- Many designers and engineers are excited about the potential for mass timber (a new category of wood product comprised of wood panels nailed or glued together) to replace steel in high-rise buildings up to 18 stories tall. Wood, from a sustainably-managed forest, is a renewable resource with a lighter carbon footprint than steel.

Why don’t we have more options?

In an ideal world, we would have hundreds of options for sustainable building materials. But we don’t yet. Aluminum is a lightweight, durable building material with a high carbon footprint. But, for now, the only sustainable option is to maximize the amount of recycled content in the material. The good news is that, as consumers, designers, builders, and owners, we have the ability to incentivize manufacturers to keep developing good options, by using our specifying and purchasing power.

Interface, Inc., a global flooring company, is a leader in sustainability, and it is worth considering their story. In 1994, Interface set out to reduce, or eliminate, their negative impact on the environment. After analyzing their carpet manufacturing process, they realized that the largest problem they had was with nylon carpet fibers — a component they did not manufacture and, therefore, had no control over. Their suppliers told them that it was impossible to produce a recycled nylon fiber, so they issued a challenge. Whoever could include a percentage of recycled material in their product would get ALL of Interface’s business. So, the next year, a company managed to introduce 2% recycled material into their fibers. And they got the business. A second company then upped the game by adding 7% recycled content. And Interface switched all their business to that company. And so on. Until now, the nylon fibers Interface uses are 100% recycled, and the company has announced that they are the first flooring manufacturer to sell all products as carbon neutral across their full life cycle.

We have to move the needle on carbon emissions, and we can only do it with a commitment to innovation, to changing the way we have always done things, and to our future generations.