This blog is part two of the latest in our “Architecture in Practice” Series. If you didn’t catch the first part of this post, start here.

Why houses cost so much in Los Angeles

We were SO excited to officially own the lot, and somehow, we came up with a design approach almost immediately. (Fun fact: this part does not always come easily.) It was meant to be!

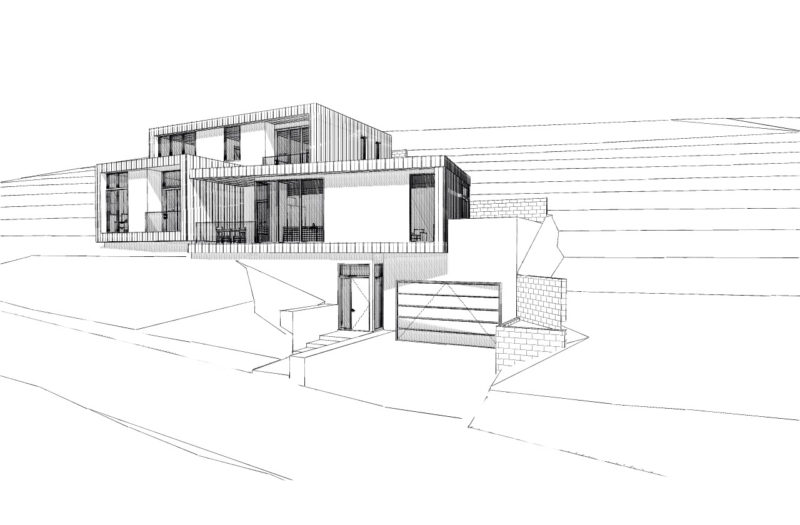

Next thing you know, we have a working set of drawings, a structural engineer on board, and then the project came to a screeching halt. We quickly realized the reality of hillside construction. The zoning code limits the height, setbacks, and maximum grading amounts (see previous post for specifics). To counter the height issue, we had decided to push the building into the ground which triggered serious amounts of shoring.

Shoring is the process of retaining earth during construction when you need to dig straight down more than 5’-0″. Why can too much shoring kill a project? It’s expensive. Thanks to our multi-story home that’s literally tucked into the hill, we were talking over 20’-0″ at some areas. OUCH!

In conclusion, here is what we were learning: development is no joke and a lot of work. Trying to marry cool design with a budget that actually pencils out is not easy.

Aren’t you guys architects? Didn’t you already know shoring was a given?

Let’s take a step back and discuss the various trades that influence design.

First, a geotechnical engineer does an investigation by digging holes and pits to evaluate the soil and earth makeup of the site. After lots of tests, the engineer can provide weight and pressure values they feel are appropriate for each site’s specific geological makeup. Next, structural engineers take those values and apply them to the elements (i.e., concrete walls, shoring design, steel sizes, etc.) they want to use for the structural design.

The types of soil found on-site greatly determine how strong the walls/resisting elements must be. For a really nice, hard bedrock, there are times when it can have unsupported cuts up to 20+ feet. Alternatively, think about sand – if you try to dig a hole at the beach, it just crumbles and has nearly zero stability on its own. While we hoped and dreamed for the strongest bedrock there ever was, we were unfortunately met with a semi-stable bedrock material called shale. It was perfectly fine for supporting a single-family house with a typical foundation, BUT, the requirements to hold back the earth at our retaining wall were huge.

After the structural engineer ran some calculations, we realized the steel required to support the hillside would be out of the question. For the 23’-0″ vertical cut at the back of our garage, we’d need W27x146 that is 66 feet long. For the non-steel fluent, that means an I-shaped steel member that is 23 feet tall above the lowest excavation, weighs 146 lbs. per foot, and also has an additional 43 feet completely embedded into the ground. All we could say was “HOLY GUACAMOLE BATMAN.”

We immediately got a little spooked and decided to reach out to a past colleague who does cost estimates to translate all these numbers into a price. Long story short, we were so beyond our budget we had to take a pause and evaluate the design, the site constraints and see what we were missing. There had to be a solution to get both a great house and meet the budget, right?

Back to the Drawing Board

Hi, we are Tracy A. Stone Architect and we are addicted to good design. (crowd: Hi, Tracy A. Stone Architect!)

When the estimate came in $600k more than we’d hoped, we had to go back to the drawing board. We re-read some of the code language and reviewed the plans more thoroughly to find ways to reduce the shoring and grading quantities required.

After a few re-design iterations and analysis, we were able to come up with three solutions:

- Shift the building to the right where the slope is less steep, lowering the amount of retaining needed

- Raise the building out of the grade a bit, which in turn will allow us to “grade” the site instead of expensive temporary shoring

- Stack the building more so the floors overlap more (i.e., fewer lineal feet of foundation)

In our last post, we noted the ability to do a “yard determination” through City Planning to figure out which side of the house was considered the front yard. We got the best news about $200 and a couple weeks later: the left side of the house facing a paper street was considered our front yard.

With that determination, we were able to do all three of the items above: lift the building out of grade, shift it on the lot to minimize retaining, and better overlap the floors. The results of these three items significantly reduced both the grading and any potential shoring requirements. In fact, it saved so much grading, that we could use the traditional grading method, if needed, meaning little to no shoring would be required.

With that determination, we were able to do all three of the items above: lift the building out of grade, shift it on the lot to minimize retaining, and better overlap the floors. The results of these three items significantly reduced both the grading and any potential shoring requirements. In fact, it saved so much grading, that we could use the traditional grading method, if needed, meaning little to no shoring would be required.

Notice the difference in design? Updated Design (below), Original Design (right)

Counting on Savings

Counting on Savings

Now that we have some revised plans (and hopefully significant savings), we’re back to engineering to see what difference this revised design will make on the structural/shoring front. Stay tuned to see if we have better results this time around.

New to this journey? Check out some of our past posts in the Architecture In Practice Series:

- Making of a Sausage… or a New Hillside Home

- 5 Red Flags When Looking for a Vacant Lot

- The Story of a Spec House in a Cookie-Cutter Neighborhood

- Architecture in Practice