It’s a common question: Why is housing in Los Angeles so expensive? We are constantly asked this question by clients and decided to dig deep to see what drives the high housing costs across the city. The answer is complex, and sometimes polarizing, because there are multiple underlying factors. The goal of this article is to simplify a few of these answers for ourselves and for others.

For sake of this affordable housing series, we’re going to start by looking at two critical factors that impact housing costs:

- 1.0 Low Supply of Housing

- 2.0 Rising Construction Costs

In our next article, we’ll dig into some recent state/assembly bills in California aimed to improve the infamous housing shortage. We’ll wrap up the series by showing some real case study examples of how these bills have affected some of Tracy A. Stone Architect’s affordable housing projects.

1.0 Why does Los Angeles have a low supply of housing?

The simple answer: California has not built enough housing to keep up with growing demand, especially in coastal metros areas (Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Jose, San Diego, Santa Barbara, etc.). For reference, it’s estimated that statewide, California is short one million to 3.5 million units, with an estimated shortfall of 450,000 in Los Angeles alone.

The imbalance between supply and demand resulted from strong economic growth that created hundreds of thousands of new jobs and insufficient construction of new housing units to meet the demand. For example, from 2012 to 2017 statewide, for every five new residents, only one new housing unit was constructed. The disparity in coastal metro areas, where the majority of job growth has occurred, is even greater.

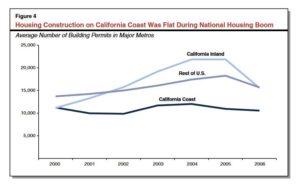

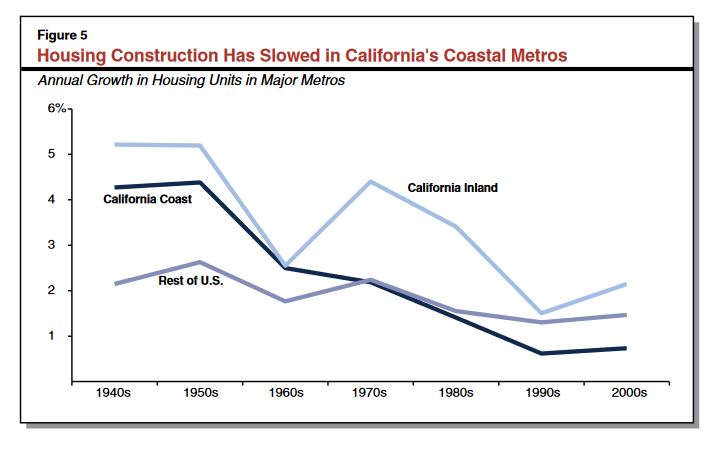

Supply and demand? Is it really that simple? Well, yes, and no. It’s true: California isn’t building housing fast enough, and even worse, it hasn’t been keeping pace since 1950 (more on that later). More recently, during the mid-2000s, housing prices were rising throughout the country, and in most locations, developers responded by building more housing. As Figure 4 shows, new housing construction in California remained stagnant in its coastal metro compared to the rest of the state.

So, what’s up with California? Why can’t it build fast enough? This answer is the result of several factors dating from World War II to the 2008 recession. There are many barriers that have slowed housing construction, but for the sake of this article, again, we’re going to focus on just a few contributing factors*:

- California’s History of Rejecting Affordable Housing

- State has Lacked Coordinated Housing Plan and Oversight

- Single-Family Zoning Problem

*Each of these could warrant their own article, but to keep this digestible, we’ll be hitting just a few high notes.

1.1 California’s History of Rejecting Affordable Housing

California has a unique and complicated history involving housing which has set the stage for our current urban planning woes, and continues to set the tone for the attitude behind housing in general. Bear with me, this next part is going to cover a little Los Angeles history, but I promise it’s interesting (Go Dodgers!)

When World War II ended, Los Angeles expected a major expansion of housing through the Housing Act of 1949; however, it never happened due to Article 34, a state constitutional provision that requires cities get voter approval before they build affordable housing funded with public dollars.

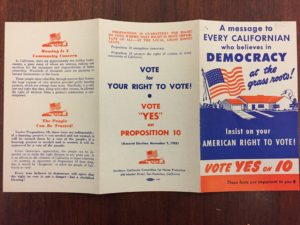

In 1950, Article 34 was spearheaded by the California Real Estate Association (known today as California Association of Realtors). They campaigned on a “Right to Vote” message, which appealed to racist fears about integrating neighborhoods as well as other looming fears of socialism.

According to the California Constitution Center at UC Berkeley’s law school, no other state constitution similarly requires voter approval for publicly-funded housing.

The initiative was narrowly passed and was a pivotal piece of legislation leading to one of the most defining events in Los Angeles History. In 1952, voters rejected a large-scale public housing project planned for the Mexican-American neighborhood known as Chavez Ravine. The project was going to house 3,300 families in a complex of 24, 13-story towers and 163 two-story garden apartments designed by architects Robert Alexander and Richard Neutra.

As many know, this situation was handled poorly by the city—mainly offering residents below-market cash offers for their homes, which led to their distrust in the government, further leading to the demise of the project. Then in 1953, with the support of Citizens Against Socialist Housing (CASH), Republican Mayor Norris Poulson was elected on a platform based largely on opposition to providing public housing—claiming to do so would be “un-American.” Most notably, Poulson led the drive to lure baseball’s Brooklyn Dodgers to Los Angeles. As a result, homeowners were evicted from Chavez Ravine, no new housing project was approved, and by 1959, the land was acquired by the Dodgers to build a new stadium.

What were the impacts? Article 34 hindered low-income housing in California for decades and weakened efforts to integrate suburban communities across the state. By 1969, California voters had turned down nearly half the public housing that was proposed. Subsequently, many housing agencies stopped proposing affordable housing solutions for fear of rejection from voter communities.

Today, Article 34 is less of a roadblock, but by stymieing public housing early on, it limited different avenues of housing that could be built. Public housing wouldn’t have been the “fix all” solution, but it would’ve helped supplement the housing supply by adding housing that wasn’t built for profit.

Additionally, this type of legislative provision set the stage for modern day NIMBY-ism by emphasizing the “local control” argument that is prevalent in California housing policy today.

P.S. The push to repeal Article 34 is still happening! There will be a ballot measure in 2024 and it will be the fourth time that lawmakers have asked voters to remove or weaken the provision, with the most recent attempt in 1993.

1.2 State has Lacked Coordinated Housing Plan and Oversight

In 2020, a report from California State Auditor, Elaine Howle, made headlines when it was made known that the state mismanaged $2.7 billion in tax-exempt bond resources—bonds that would’ve likely helped Gov. Gavin Newsom move closer to his target of adding 3.5 million homes.

How does something like that happen? For decades, the state has lacked a coordinated housing plan, resulting in mismanaged housing resources. Additionally, the state has lacked oversight to compel cities to build enough affordable housing to keep pace with the growing economy.

Due to legislative provisions over the years, such as Article 34, housing in California has been mostly left to the private sector. Developers will pick and choose when and where to build, and they will not build if there isn’t a profit. It sounds simple enough.

So, how do we incentivize developers to build affordable housing? There are two common scenarios:

- Due to high land costs, developers typically opt to build luxury housing. Recently, those types of developments have been incentivized to include affordable units in exchange for density bonuses*. This is a great strategy, but it only goes so far, since density bonuses are often subjected to review by neighborhood councils, environmental analysis, and community concerns, which in turn, slow or even halt projects, increasing costs and construction timelines.

- If developers choose the other route and apply for state resources to fund affordable housing projects, developers are subject to cumbersome processes and must apply to multiple agencies, all with inconsistent requirements, which in turn, slows projects and increases project costs. (Do you notice the pattern here?)

*Projects can request up to a 35% density bonus and/or reduced parking specified by the State Density Bonus law with no discretionary review, no CEQA review, and not subject to appeal.

Developers play a big role in our housing supply, but State legislature has declared that “private investment alone cannot achieve the needed amount of housing construction at costs that are affordable to all income levels.”

What does the state have planned? The current 2022 Statewide Housing Plan lays out California’s vision to meet its goal of adding 2.5 million homes over roughly eight years, with no less than one million of those homes targeted for lower-income households. This represents the cumulative number of homes that cities and counties across California must zone for through 2030 by law and is more than double the housing planned for in the last eight-year housing needs cycle.

How will this play out in Los Angeles? Prevalent in Los Angeles is heightened community resistance to new housing, especially affordable housing, but what is unique is their ability to fight housing on multiple fronts with no intervention from the state (however, this is changing—again, more on that later).

In general, it is common for local residents to be concerned about new housing throughout the U.S. Existing residents cite the many potential downsides of new housing (property values, construction noise, increased traffic), while the many benefits of new housing accrue to future residents. As a result, existing residents sometimes take steps to slow or stop development, which subsequently drives up housing costs even more (Do you see the pattern now?).

According to the 2015 Legislative Analyst’s Office report, incidents of residents directly interfering with land use decisions occur more often in California’s coastal metros compared with the rest of the country. For example, over two-thirds of cities and counties in California’s coastal metros have adopted policies (known as growth controls) explicitly aimed at limiting housing growth.

According to the same 2015 LAO report, one study of growth controls enacted by California cities found that each additional growth control policy a community added was associated with a three- to five percent increase in home prices. Now imagine how much those policies and prices have snowballed the past half century.

Above: Figure 5 from the 2015 Legislative Analyst’s Office report

Why is this important? If cities can’t rely on private developers alone, then the state needs to set cities up for success by providing a cohesive plan that streamlines local administrative processes, as well as state administrative processes to acquire state-funded housing resources. To help solve the housing shortage, it should be easier to build state-funded affordable housing than it is to build luxury apartments.

The state has recently enacted many, many bills related to housing, has reformed CEQA bills, and is actively removing barriers to development by providing resources for local planning efforts to accelerate housing construction. This is good news, but Los Angeles still has a few of its own obstacles to overcome. Specifically, we need to look at its single-family zoning problem.

1.3 Single-Family Zoning Problem

Typically, when you think of big cities, such as New York or Chicago, you picture people living in apartments near walkable amenities. When you think of Los Angeles, the second most populated city in the U.S., most of us picture the antithesis to urban living: single-family homes and two-car garages.

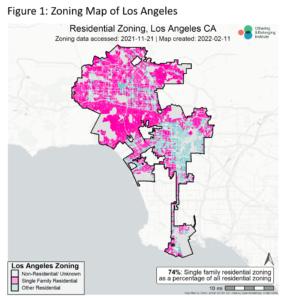

This leads us to the fiercely debated topic of Zoning Ordinances in Los Angeles, which The Othering & Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley has called “hostile to density and are now recognized for their role in halting production of affordable housing, contributing to homelessness, and in sustaining racial and economic exclusion.” (article)

When it comes to housing supply in Los Angeles, it’s easy to see the direct effect zoning laws have made. Today, developers are limited to mostly low-density projects, which doesn’t do much when it comes to offsetting the high cost of land—land that is already scarce for development.

How did we get into this predicament? In 1920, the city introduced its first zoning code. Most notably, less than 5% of the city’s zoned land was exclusively restricted to single-family homes up until 1933. Most residential properties at that time fell under a more flexible zoning designation that allowed for many different types of construction, including bungalow courts and small multi-family developments that can still be found in older neighborhoods today.

In the following decades, LA’s zoning rules became more restrictive and more car-centric. By 1970, almost half the city was zoned for single-family use only, according to Greg Marrow, director of UC Berkley’s Real Estate and Design program. Now, 74% of residential zoning in Los Angeles is zoned single-family.

What changed? Congress passed the Housing Act of 1934, which was passed as part of the New Deal during the Great Depression in order to make housing and home mortgages more affordable. Since taxpayers would be responsible for funding the mortgages, the Federal Housing Administration went to great lengths to minimize the risks of the loans.

Often this meant that “safe investments” were neighborhoods that consisted of entirely white residents. In response to these lending policies, city planners across the U.S. sought to make their single-family neighborhoods safe investments by utilizing exclusionary zoning and creating barriers for low-income families. The effects of this were particularly felt in cities like Los Angeles, where the city was still young and there was plenty of vacant land at the time.

By the 1970s, local leaders constrained new development further, seeking to slow LA’s growth by limiting the amount of housing that developers could build (Remember those growth control policies mentioned earlier?).

Multiple studies conducted by The Othering & Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley found a disturbing relationship between the degree of single-family zoning, racial demographics, and racial segregation. Their research supported the theory that restrictive zoning has been a “mechanism of opportunity hoarding,” which in our case, has directly resulted in a low supply of housing.

In conclusion, the low supply of housing in Los Angeles is the direct effect of multiple factors that have inhibited the construction of denser developments. The one underlying theme that can’t be ignored is that the people of Los Angeles have simply, and historically, not wanted to build housing for everyone. Now the current housing shortage represents years of racist policies and opportunity hoarding.

In Summary:

Why does Los Angeles have a low supply of housing?

- California has a history of rejecting public housing.

- Legislative provisions, such as Article 34 of the state constitution, have allowed voters to block different avenues of housing for decades

- No other state constitution has had a provision that requires voter approval for publicly-funded affordable housing

- Today, California housing is still being stymied by the “local control” attitude of neighborhoods

- State lacked coordinated housing plan and oversight to enforce it.

- Due to lack of coordination between agencies, the state has been mismanaging housing bonds for years with little accountability

- Lack of a coordinated plan has left housing mostly to the private sector, but private investments alone are not enough to meet construction needs

- Years of local growth control policies and residents’ involvement with land use decisions have significantly slowed housing construction, with little to no intervention from the state

- Los Angeles has a single-family zoning problem.

- Single-family zoning in Los Angeles is outdated and based on racist policies

- Today, 74% of residential zoning in Los Angeles is zoned single-family

- Land in California is expensive, and developers are mostly limited to low-density housing projects which are not enough to offset high land costs or keep up with housing demands

Have you satiated your need for knowledge of the housing crisis? If not, there’s more:

Want to stay up to date? Make sure you are subscribed to our newsletter below.

Sources:

California’s High Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences (Legislative Analyst 2015) – https://www.lao.ca.gov/reports/2015/finance/housing-costs/housing-costs.pdf

California State Auditor 2020 Report – http://auditor.ca.gov/pdfs/reports/2020-108.pdf

How did 2.7 Billion in housing bonds disappear? https://calmatters.org/california-divide/2021/03/california-affordable-housing-bonds-disappear/

City Planning Annual Report 2022 – https://planning.lacity.org/odocument/1b3b63d3-1f30-4c14-a82d-9902db0864d6/202211_AnnualReport2022.pdf

LA Times: Why its been so hard to kill Article 34, California’s racist barrier to affordable housing – https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2022-03-14/why-killing-article-34-on-affordable-housing-has-been-hard

Single-Family Zoning in Greater Los Angeles: https://belonging.berkeley.edu/single-family-zoning-greater-los-angeles